Five-eighth Fred May was the Luke Keary of 1940; a premiership-winning No. 6 from Eastern Suburbs who helped steer the club to a second competition decider the following season.

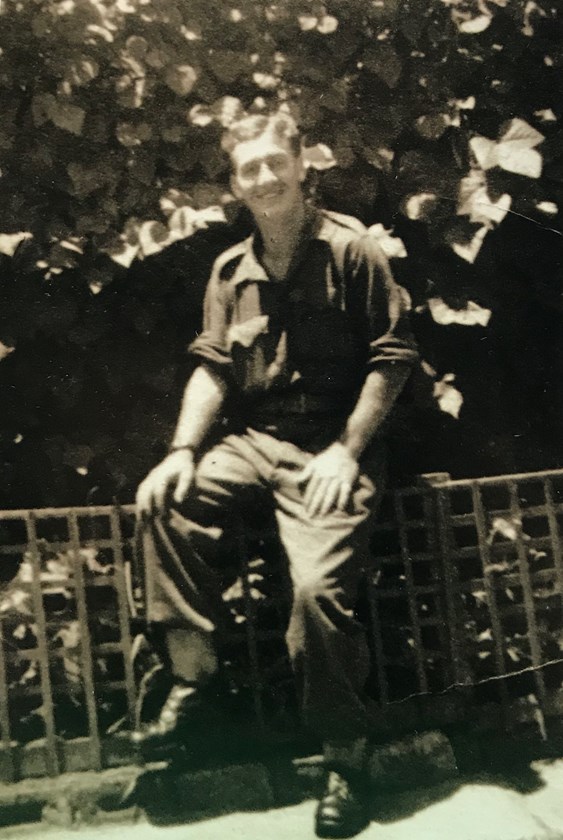

Aged 24 24, May enlisted in the Australian Army in January 1942 and three years later he was killed in action in New Guinea.

But unlike most prominent league men who gave their lives for their country, May received next to no recognition in the years that followed.

Most former players who paid the supreme sacrifice have been well documented in newspaper articles and club histories.

The recent centenary of World War I brought to light the stories of many of the men who were once idolised by the public on the sporting fields of Sydney and Brisbane and who later gave their lives for their country.

Former players killed in World War II, such as Jack Lennox, Peter Hickey, Len Brennan, Jack Redman and Spencer Walklate have featured prominently in print and have been honoured in various ways down the years.

Lennox, for instance, had a schoolboy competition named after him, while the Peter Hickey Cup featured in the Brisbane premiership for many years following World War II.

It was a different story for Fred May, whose family, including son Jeff, who was three when his father died, could never understand why his name was left off memorial rolls and effectively forgotten by rugby league.

Perhaps the sporting public was numb with grief at the constant listings of dead and wounded soldiers. By early 1945, the war had dragged on for almost six years and few had the stomach for more bad news. Also, after Easts lost to St George in the 1941 final, Fred and his young family moved to Newcastle where Fred became publican at Hamilton’s Kent Hotel before enlisting.

Another factor was the retirement of Eastern Suburbs’ long-term secretary John Quinlan in 1944. It is hard to believe that May would have been forgotten had he remained on the scene.

May had a rugby league pedigree. His father, William ‘Wilbur’ May had played first grade at Glebe and was a contemporary of Immortal Frank Burge. Fred played his early football with St James Sports Club at Glebe, which became a junior club of Balmain after the Dirty Reds were eliminated from the premiership in 1929.

May shifted residence to the eastern suburbs in the late 1930s and played his way into first grade when he was 22, figuring in all of Easts’ games on their way to the 1940 premiership final victory over Canterbury. The glory days of Easts’ 1930s successes were waning, and captain-coach Dave Brown, who had returned after three seasons with Warrington, missed the final through injury. Easts’ strength lay in their forwards, where Kangaroo stars Joe Pearce, Ray Stehr, Andy Norval and Harry Pierce formed the nucleus of an imposing pack.

May and halfback Sel Lisle were instructed to play to their forwards and both won praise for their unselfish efforts in the 24-14 victory. A year later Easts returned to the final, but despite the same pairing in the halves, the return of Brown at centre, and Pearce and Stehr remaining up front, they were no match for a St George team who claimed the club’s first top grade title with a 31-14 win.

It was before the 1940 decider that May earned his first taste of representative football, turning out for a Combined Metropolitan team (effectively City Seconds) against Combined Newcastle at Newcastle Sports Ground. City and Country (Firsts) met in the annual clash at the Sydney Cricket Ground on the same day.

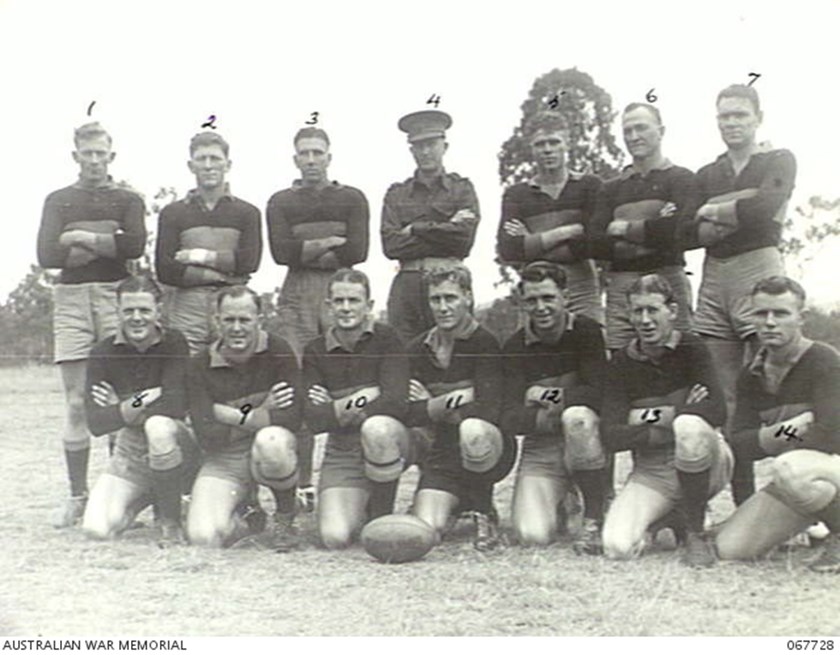

May continued in rugby league even after enlisting in the Army in 1942. He turned out for the 2/3 Machine Gun Battalion that lost to the 2/3 Infantry Battalion in the 6th Division rugby league grand final of 1944.

In 1945 May’s battalion was involved in the “long and exhausting” Aitape-Wewak campaign on the north coast of New Guinea. By March of that year the Japanese were largely on the defensive and operations were described as a “mopping-up campaign”, with troops required to empty the heavily forested and mountainous region of the remaining enemy forces. Author John Bellair, whose book From Snow to Jungle describes the history of the battalion, stated “When they [the Japanese] attacked they fought well, though their supply problems of rations and ammunition was becoming serious.”

He described May’s fate in an attack that took place on a jungle track. “On 13 March, a 10 Platoon patrol was ambushed on a track running along a razorback. The enemy had the track covered by one of their Juki heavy machine guns and by another lighter, automatic weapon. Corporal F.R.May, Privates R.M.White and R.C.Gordon were killed … ” Four other privates were wounded, one dying of his wounds within a week.

News of May’s death was reported in the Sydney press 10 days after the attack. The Sydney Morning Herald afforded three lines buried deep within a rugby league column, while the Daily Telegraph at least accompanied four lines of news relating to his death with a sub-heading, “League Player Killed”.

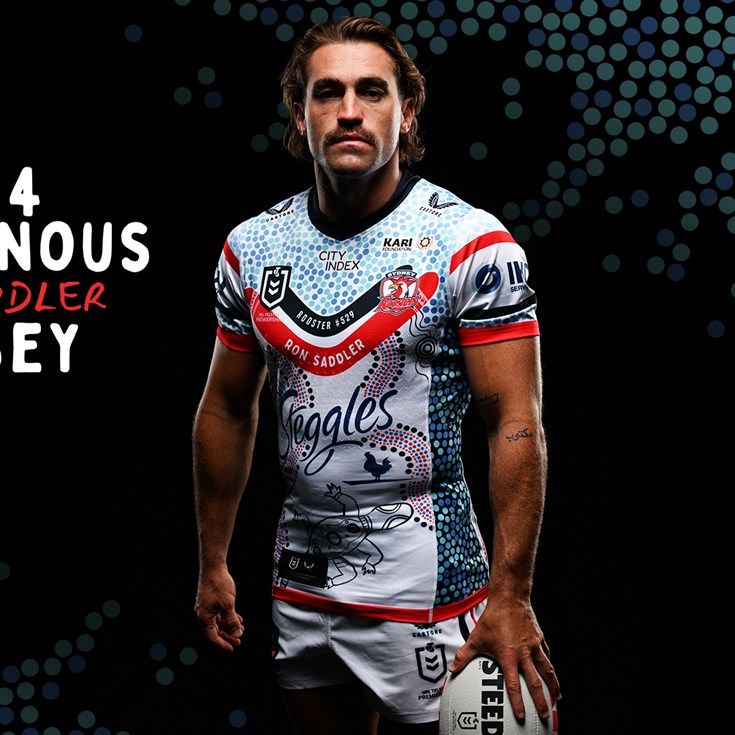

Thankfully, the Roosters of 2019 have a coach with a deep regard for history and on hearing that a premiership-winning former player who gave his life for his country had been effectively overlooked, Trent Robinson did not hesitate to reach out to the family.

May’s son and grandson will be honoured guests at the Anzac Day clash at the Sydney Cricket Ground and were invited to attend the Captain’s Run and meet Roosters players before the game.

Recognition has been a long time coming but finally, Fred May will no longer be rugby league’s forgotten soldier.

Written by Dave Middleton for BIG LEAGUE.