As we approach tonight's clash against the Dragons and commemorate the Battle of Lone Pine, here's a snapshot of why we remember this important moment in ANZAC history.

Allied forces planned the August Offensive as a complex series of actions to take control of the Sari Bair Range from the Ottomans.

As part of the offensive, Lieutenant General Sir Harold Walker commanded Australian troops to launch a diversionary attack at Lone Pine. The site on 400 Plateau was south-east of Anzac Cove and named for its height above sea level.

What was the purpose of the Battle of Lone Pine?

One of the most famous assaults of the Gallipoli campaign, the Battle of Lone Pine was planned as a diversion from attempts by the Australian and New Zealand units to force a breakout from the ANZAC perimeter on the heights of Chanuk Bair and Hill 971 which became known as the ‘August Offensive’.

The Turks shelled the overcrowded ANZAC lines just before the charge. The Australian forces, consisting of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th Battalions entered the main Turkish trenches within half an hour.

The 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th and 12th Battalions reinforced the first Brigade the next day and the battle raged for four days.

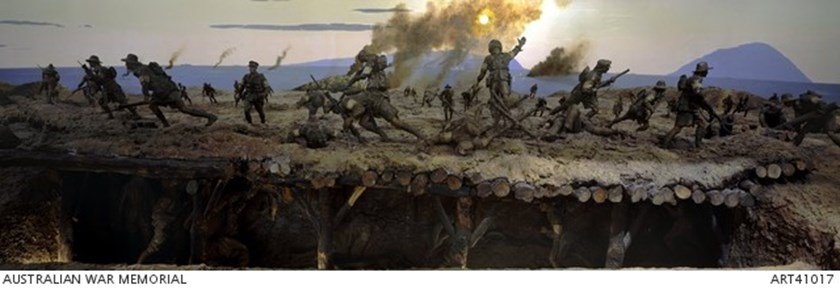

It was in this log covered trench complex, in total confusion, amid screams of anguish and despair, Lone Pine became a furious nightmare of hand to hand combat. "We were like a mob of ferrets in a rabbit warren" one trooper said. "It was one long grave, only some of us were still alive in it".

An Australian artillery barrage of Ottoman trenches preceded the attack.

At 5.30pm on August 6, 1915, the attack began. With the evening sun slanting down into Turkish eyes, the Australians rose from their trenches and charged.

The Australians' objectives were to:

- Take and hold the Turkish line

- Draw Turkish reserves away from the action on the Sari Bair range

When the Australians reached the Ottoman line, they found timber roofs covered many of the trenches. At this point, they split up and either:

- Fired, bombed and bayoneted from above

- Made their way inside the trenches

- Charged past to the open communications and support trenches behind

- Advanced as far as ‘the Cup’ (about 20 metres behind the Turkish front line)

Within minutes, the Australians had seized the first Turkish trenches and were into the communication trenches beyond.

By nightfall, the Australians had:

- Taken over most of the enemy front line

- Established outposts in former Ottoman communication trenches

Then, the real battle began.

From nightfall on August 6 to the night of August 9, fierce fighting took place underground, in a complex maze of Ottoman tunnels.

Australian Engineers dug a safe passage across No Man’s Land so that reinforcements could enter the captured positions without being exposed to enemy fire.

The Turks desperately tried to eject the attacking force, but the Australians held on.

Despite the ANZAC victory, the overall August Offensive failed. A stalemate developed around Lone Pine and lasted until the evacuation of Australian troops in December 1915.

Casualties and decorations

When the battle was over, more than 2,300 men were killed or wounded across six Australian battalions, and over 6,000 Turks had been killed or wounded.

From the action at Lone Pine, seven Australians were awarded the Victoria Cross (VC), the highest British Empire bravery decoration. It was the highest number ever awarded to an Australian division for one action.

One VC went to Captain Alfred Shout of 1st Battalion, who was evacuated with terrible wounds. Despite the pain, he was ‘still cheerful and sat up to drink tea’ but died two days later. Captain Shout's name is recorded on the Lone Pine Memorial.

Remembering the fallen at Lone Pine

The Lone Pine cemetery in Turkey partly covers:

- the old battlefield

- Australian positions (behind the eastern edge)

- Turkish trenches (near the Lone Pine Memorial pylon

Why was it called Lone Pine?

Part of the Gallipoli campaign, it got its name from the solitary pine tree that distinguished the scene of the battlefield.

The Turks had cut down all but one of the Aleppo pines that grew on the ridge to cover their trenches. This tree was whittled away by shell fire in the early battles. Australian soldiers called it "Lonesome Pine" after a popular song of the time.

Although the tree was destroyed in the fighting, pine cones that had remained attached to the cut branches over the trenches were retrieved by two Australian soldiers and brought home to Australia.

Private Thomas Keith McDowell, a soldier of the 23rd Battalion brought a pine cone from the battle site back to Australia, and many years later seeds from the cone were planted by his wife's aunt Emma Gray of Grassmere, near Warrnambool, Victoria and five seedlings emerged, with four surviving. These seedlings were planted in four different locations in Victoria: Wattle Park (May 8, 1933), the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne (June 11, 1933), the Soldiers Memorial Hall at The Sisters near Terang (June 18, 1933) and Warrnambool Botanic Gardens (January 23, 1934).

Another soldier, Lance Corporal Benjamin Smith from the 3rd Battalion, also retrieved a cone and sent it back to his mother (Mrs McMullen) in Australia, who had lost another son at the battle. Seeds from the cone were planted by Mrs McMullen in 1928, from which two seedlings were raised. One was presented to her home town of Inverell (New South Wales) and the other was forwarded to Canberra where it was planted by Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester at the Australian War Memorial in October 1934.